The horse has always had an exalted position in the Ancient World. He was the animal who carried the gods and heroes. He was not a beast of burden to be used by the common peasant but rather an animal for sport and for war and on the cursus publicus. It was only when the horse lost his nobility in the Middle Ages that we find him sharing in the mundane work of ploughing a field – a task which the ancient world relegated to the ox, the mule and the ass.

Therefore both Greek and Roman artists strove to portray the horse as an animal of great spirit who shared his rider's/driver's desire for victory, frequently depicting the horse as being an active participant who is glorying as much as his rider/driver in winning the race, or the battle. It was almost an anthropomorphic view of the horse. The artistic representation of these emotions displays the animal in an excited state galloping proudly forward with mouth open and head held high and proud.

However, not all writers on the topic have seen the artistic representation thus. In fact they used these artistic artifices to reinforce their views on other issues of the civilization such as the quality of the harness. They applied these unfounded views even to images where the horse is not even harnessed. Gimpel writes on artistic convention as follows:

As soon as the horses started to pull, the neck straps pressed on their jugular veins and windpipes, strangling them and making them throw their heads back like the horses of the Parthenon. Lovers of Greek art have always celebrated the rare genius of the Greek sculptor who gave such dignity to the horse, without realizing that the horse they celebrated had his head raised to avoid strangulation. 1

For purposes of comparison I show here some of the horses from the Parthenon. These images can be found at the following web site.2

Fig. 25: Pediment

Fig. 26: Pediment

Fig. 27: Frieze

Fig. 28: Frieze

Fig. 29: Frieze

Fig. 30: Frieze

I am sure that another reason the horse's mouth was often open was the severity of the bits used in Antiquity, especially in racing. We have only to look at the reaction of horse to having pressure applied by the reins while bridled with an ancient Newstead bit3 to realize that the expression is similar to that seen in so much ancient iconography of war-horses and chariots. As you can see from Fig. 31

Fig. 30: Newstead Bit

Fig. 31: Reaction of horse when Pressure applied to bit

The horse opens it mouth to protest the pressure of the bit. Pelagonius in his Ars Veterinaria tells of treating severed and torn tongues on the horses used in race due to the severity of the bits. It was rather the severity of the bit which caused the horse to open its mouth rather than any problem with the yoke harness. And as for the question of the heads being elevated to help them breathe we must turn to the question of artistic convention. We must not forget the role that artistic convention plays in the depictions from various ages. To depict a team of horses in the 18th Dynasty in Egypt – the outline of the 2nd horse was shown just outside the carving of the first horse. In fact this form of outlining was the standard way to depict multiple beasts. When the classical conventions changed as in Roman times, the emphasis was on more natural presentation. Hence to show teams of horses often the inner horse is depicted with its head elevated above the outer one4. Nor must we ever lose sight of the fact that what we see also contains the limitation of the sculptor as to his ability to render correctly the proportions of what he is depicting or even modifying them to fit into the area designated for the image5.

This posture can be seen in horses on the Parthenon who are wearing NO harness at all. As matter of fact so popular was this representation of the horse, that it continued through the ages and can still be seen in the paintings of the modern day. In these modern day paintings, we still see the horse charging at Quatre Bras6 with its mouth wide open, eyes bulging, and spittle flying. Similar representations of horses in battle can also be observed in paintings such as Berkeley's Omdurman, or Georges Scott's Elandslaagte or Charlton's painting of French Artillery crossing the Aisne7.

Fig. 32: Quatre Bras (Black Watch At Bay) by James B. Wollen. (1857-1936)

Fig 33: Detail of horse head from Figure 32

So popular was a high head carriage that in Victorian days, coach horses were cruelly subjected to the check rein, so aptly portrayed in Anna Sewell's Black Beauty, to give them a much sought after head position.

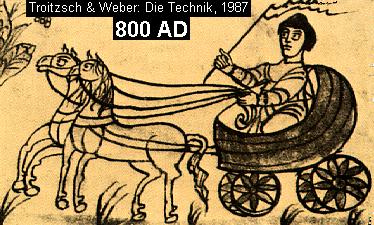

Nor is the difficulty in interpreting art from the point of view of analyzing the technology restricted to antiquity alone. Things don't really improve in the Middle Ages. Catherine Rommelaere reminds us that the images we see on tapestries, miniatures, bas-relief are very often imprecise, since the artists were ignorant of the laws of perspective, and any sense of realism8. This is especially true of the early Medieval Period where the horses do not even appear to be attached to the cart other than by magic (see Figure 34.).

Fig. 34: End of the 9th Century9

Fig. 35: Bayeux Tapistry10

Fig. 36: First half of 10th century11

More importantly Rommelaere points out that it is only in the Bayeux Tapestry (see Figure 35) that we can, for the first time, clearly distinguish the horse collar12.

Fig. 37: Trier Apocalypse13

The earlier images such as the Trier Apocalypse, which some consider to be the first evidence of a horse collar, do not show a well defined harness. The evidence for it being a horse collar is based on what some say are the supple traces which were part of the development of the horse collar.

Fig. 37: From manuscript dated 102814

Yet even in the first half of the 10th century there appear images in which shaft appear to be fixed to some sort of neck collar on the horse15 which seem to more closely resemble the neck yokes of Roman Gaul than the medieval horse collar. Fig. 37 continues to illustrate the artistic problems with the horse collar. Except for the what could be supple traces this images looks very little different than those on the funerary monuments Raepsaet studied. But can we be sure that the Romans did NOT have supple traces? Or are we seeing just poor art and the harness is the Gallo-Roman neck yoke? After all in the quadriga the outer horses were attached with a supple trace. From an artistic point of view there appears to have been a long period of several hundred years when Roman traction methods existed side by side with the horse collar.

- Gimpel, pp. 32-33

- http://rethymno.forthnet.gr/marbles/

- Figures 30 and 31 are from Hyland, plates 10 and 14.

- Raepsaet, 1982, p. 233

- Ibid.

- The original painting hangs at the Black Watch museum in Perth, Scotland.

- Harrington, passim.

- Rommelaere, p, 76

- Ibid., p. 89

- Ibid., p. 91

- Ibid., p. 90

- Ibid., p. 81

- Troitzsch & Weber

- Dixon. An early 11th-century manuscript (dated 1028) of Archbishop Raban Maur's On the Universe, (Monte Cassino, Italy, 1028) a 9th century encyclopaedia drawing its material from both Classical and theological sources."

- Rommelaere, pp. 81, 90